Legacy EDI to a cloud enabled platform

We replaced an entire mainframe with a couple of adapters; here’s what happened.

Back in 2011 we needed to replace a legacy mainframe system for a customer. They were in effect acting as a Value Added Network (VAN) in a small industry and needed to completely replace legacy hardware and out of support software; essentially they were trading two types of data, EDI (X12) and a proprietary flat file format. Enough time has passed now that I can blog about it fairly objectively and use it as a case study for how we achieved the deadlines and transitioned this community to a cloud enabled platform. Our strategy for migration had to cope with no documentation and the lack of a test infrastructure for the community.

The legacy environment consisted of 3 key machines; an RS6000 running a pretty ancient version of AIX (the java version was 1.1.8), a Solaris machine running SunOS 5.x, and a mainframe system (IBM); about 80-100 PC clients had been deployed and these were running a proprietary application written in VB6 (having inspected the code, I would say that some of the code was written for VB5 or earlier even). There were some other systems that made up the suite of applications that serviced this community; a Windows 2003 instance providing SQL server, and another instance with Biztalk installed.

The way in which the PC clients communicated with the mainframe was via Sun RPC. The RS6000 handled the bulk of the other types of external connectivity which was with all the major VANs (IBM/GXS/Sterling amongst others), via a software package called Connect:Enteprise. The mainframe was responsible for managing the customer database along with data enrichment activities such as de-duplication, segment terminator modifications and reporting.

This sets the scene for the scale of work that needed to be done; it had to be done to a tight timescale; support contracts for the mainframe were up for renewal amongst other things (the most pressing thing in my opinion was there was a 72yr old that wanted to retire).

Analysis

There was only really one pragmatic approach that we could take; keep the RS6000, but remove the dependencies on the Solaris machine and the mainframe. The logic behind this was fairly straight-forward; the customer themselves couldn’t tell us which of their customers was actually using the RS6000; doing that scoping work would have taken far too long and really killed the deadline. The PC clients would be slowly transitioned to a web client, but in the interim they would be left as-is, which would mean supporting Sun RPC in the short term for these clients.

The way Connect:Enterprise was hooked up was via a number of custom shell scripts that called specific utility programs to queue messages and extract messages from incoming queues; it’s just scripting, this gave us a high degree of confidence that we could do any required modifications that we required to remove its own dependencies on the mainframe.

Doing the work

So now we know the core activities that need to take place; replace EDI de-duplication and reporting in the mainframe, and rewrite the server process so that we could get rid of the Solaris machine. The first part was pretty easy, the second part not so much.

The usual things happened during the development period; their mainframe and other systems lost power; once was due to a massive fire at the local electricity substation; we had to assist with their recovery process (it turns out that everyone who knew anything had left, which was another reason why the migration was so critical) and that burnt a lot of time that could have been better spent.

Overall design

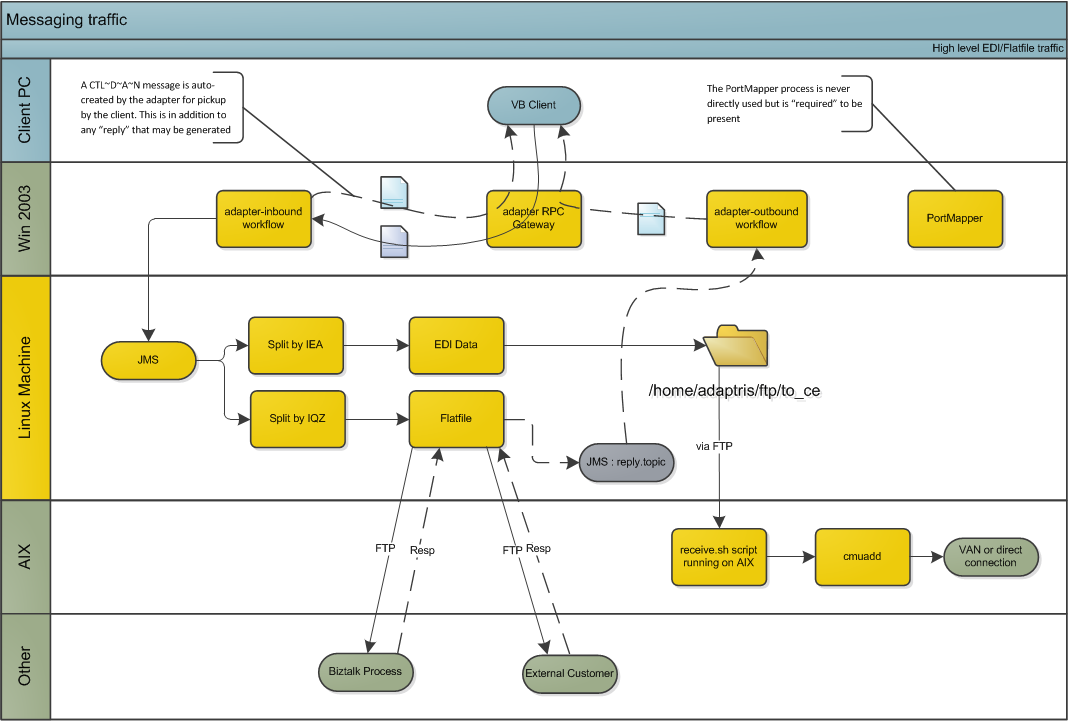

This diagram shows the key components that are in play; the names have been made fairly generic to protect the guilty and only shows data originating from the PC clients, but essentially the whole mainframe was replaced by a single Adapter instance running on a Linux machine. The SunRPC server was replaced by another Adapter instance (though it could have been the same one; we wanted to keep things loosely coupled for logging/maintenance purposes).

The major stumbling block throughout this was the lack of documentation combined with a non-existent test environment. Because this was a legacy system that been around for a long time, key developers had left to do other things (or been let go). We were in the unenviable position where we had to support the existing production system (because no-one else knew anything about it), and also to migrate the production system from the mainframe to our proposed architecture with little or no downtime. None of this is surprising to anyone who’s worked in integration long enough.

EDI/Mailbox management/Reporting

The Adapter framework has all the components already that can support most or all of this out of the box; there were a couple of custom services that were required to replace the mainframe functionality. This part wasn’t stressful at all for the technical team; it’s bread and butter for us. It was simply another Cirrus platform deployment; the only real changes were to setup a few database tables that mirrored the mainframe database (vis-a-vis customer segment terminators and the like).

Proprietary Message Format

There was very sparse documentation about this, to the extent that it made no sense whatsoever, so we had to work it out as we went along. There were arbitrary headers and trailers that were added / removed depending on various states; an apparent lack of rules around when data should have particular headers or not; plenty of random acknowledgement messages that were being sent back and forth; some of which made sense, most of them didn’t. We weren’t doing any data enrichment so we didn’t need to understand the data format, just enough of the headers to generate control messages and route the messages correctly.

Whenever I see something like this I’m always reminded of the fact that formal message definitions are something that should be left to people who care about these things (like I don’t know, an EDI standards body); never ever let a developer make up a flat-file format.

Luckily a heavy user of the system was willing to some testing for us, and using their system we captured a lot of messages that were going through the existing system. In the end, it was just a case of generating the correct data at the right time (it’s just data) which meant a couple of custom services, but in the end nothing too terrible.

Sun RPC

It turns out that there are a couple of Sourceforge projects that have tried to re-create the Sun RPC (ONC/RPC) protocol using java. None of them worked; we had to break out Wireshark and do some low-level TCP analysis. Turns out the original developer had made some poor decisions in his implementation and it wasn’t actually RFC1831 compliant. In the end our developers wrote their own implementation of the RPC protocol purely to fit this broken implementation. It wasn’t pretty, and we did take some short-cuts, but a replacement was ready in just under a month.

What made it worse was that in a a case of premature optimization the original developer had opted to use the pkware compression library (he was in fact using it wrong which caused no-end of amusement for us) to compress what turned out to be messages that were about at most 4K.

This was probably the hardest technical challenge of the entire project; due to the timezone differences, we ended up working very late nights/early mornings trying to minimize disruption to their existing environment.

Sundry odds and sods

In any project there are always sundry odds and sods that come out and bite you in the arse. For this one it was the fact that there was request reply functionality that was happening via FTP. Whenever I see something like this I always have a little chuckle at the how this is clearest example of a square peg in a round hole; we had to generate a sequence number and write documents with that sequence number onto a customers FTP server, and then poll the same directory for a response file (same sequence number). The Adapter framework will support this kind of behaviour (not that I would approve of it) so at least that was an easy one to resolve.

Post Production washout

We cut over into production in October 2011; all it required was a change to DNS. The Solaris box and the mainframe were shutdown within a fortnight of go-live. Our medium term plan was always to migrate the existing PC clients onto a web platform which allows the end users to upgrade their systems without having to worry about the legacy application; this is now 90% complete with some the final few customers being cut over in the next few months; the RS6000 is being de-commissioned, it’s taking a while, but customer migration and and the testing cycle always takes a long time. This is largely because of the seamless transition that we managed to put in place; some of the customers still think that we’re using the mainframe.

Summary

We’re an integration company; this is what we do. We’ve extended the life of a traditional ANSI X12 environment with a clear migration path towards SAAS; we’ve managed to migrate an entire community seamlessly off a mainframe with only limited interuption to their expected levels of service; we replaced a legacy mainframe system with 2 adapters, one to handle the RPC calls, and one to provide the routing and mailbox management. It was no small achievement for our team to implement and go-live this entire solution in 5 months.